Meditating can provide an inner home (OMAC training weekend in Frankfurt a.M. 2012)

Meditating can provide an inner home (OMAC training weekend in Frankfurt a.M. 2012)

While reflecting what influence my grandmothers (and my fathers) story had on me, I couldn’t help but wonder in how far my inability to really have and care for a home has some of its roots in the fear of having to leave every possession behind. I always wondered how it must have been for them to having to leave without knowing if they would ever see their home, their country, their families and friends again.

And I wondered how they managed to live all those years away from home, in a place where they did not want to be.

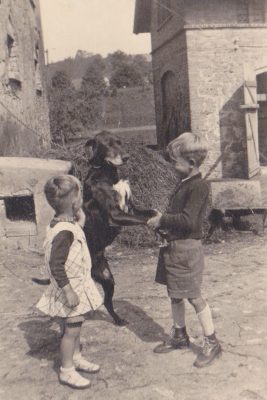

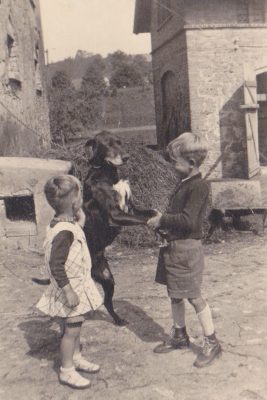

The farmhouse in Reibnitz where my father and his parents and other family stayed after they were “lagerfrei”, meaning they were “free” to live somewhere outside of the deportation camps but were still under strict control and supervision. My Dad remembers the farm house well, also the friendly dog.

Whenever I have something that matters to me, I consider how it would be to lose it. The loss is somehow already planned before I even manage to take real possession over the thing / place / home …

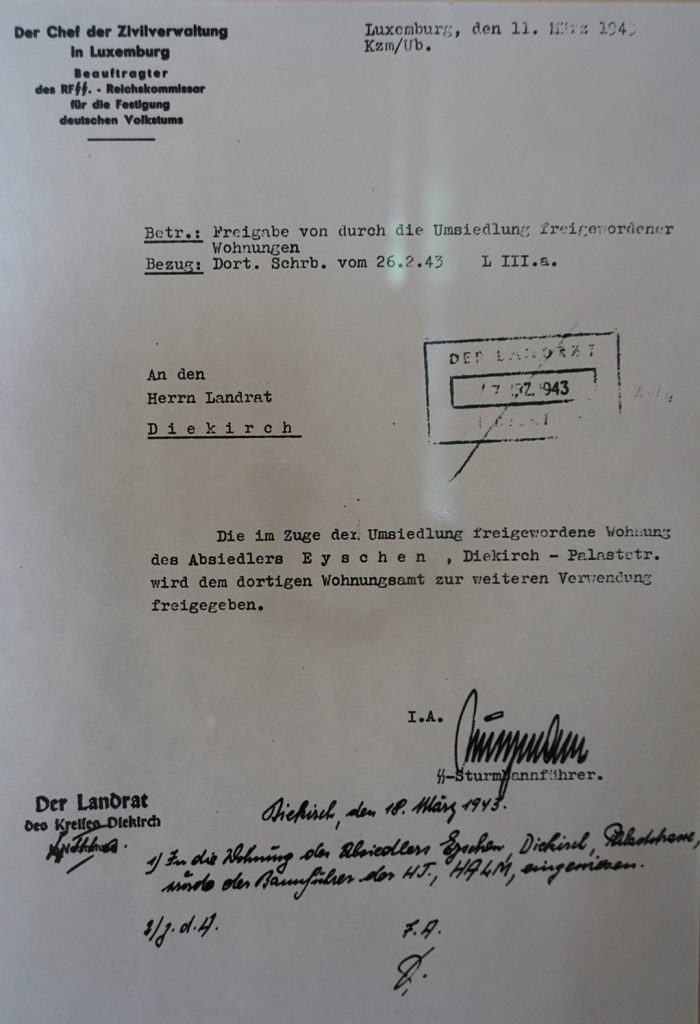

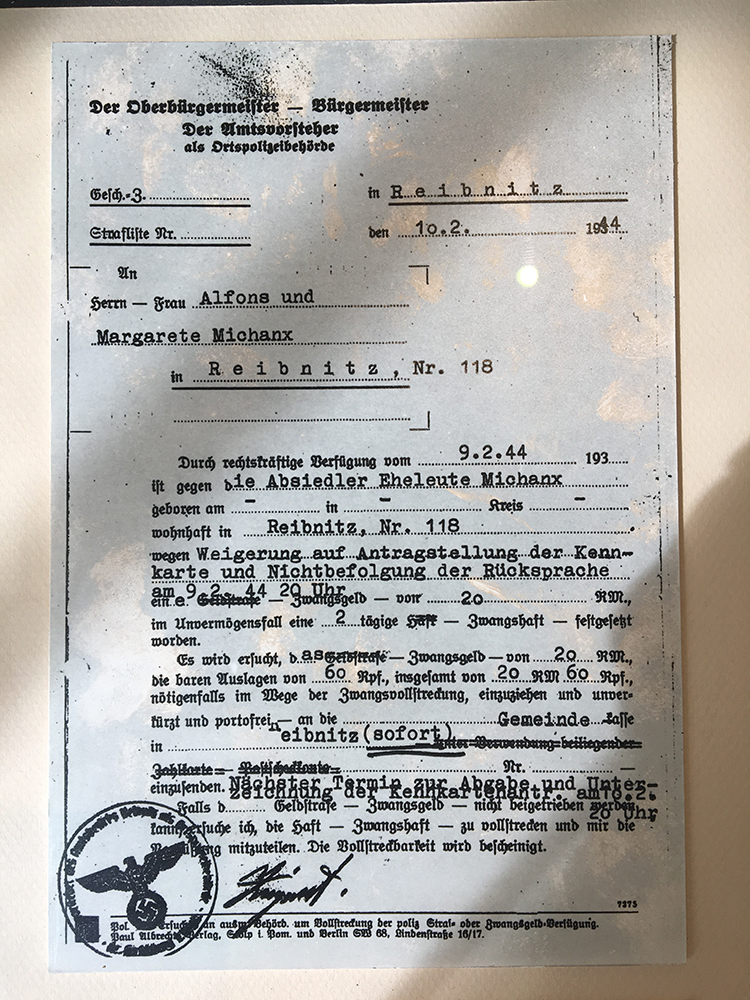

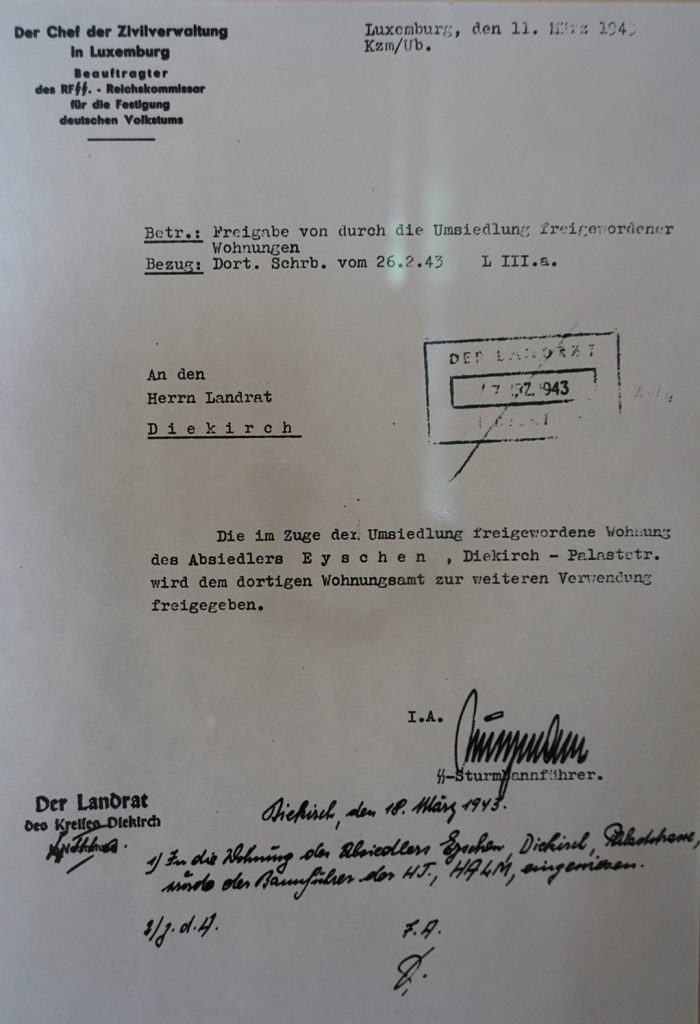

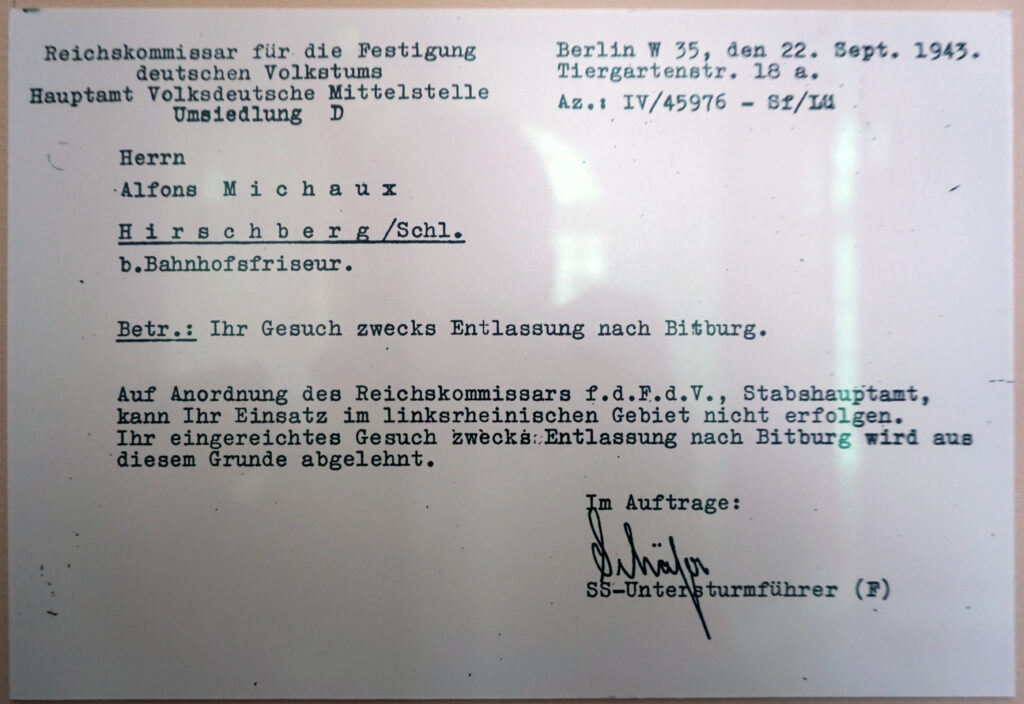

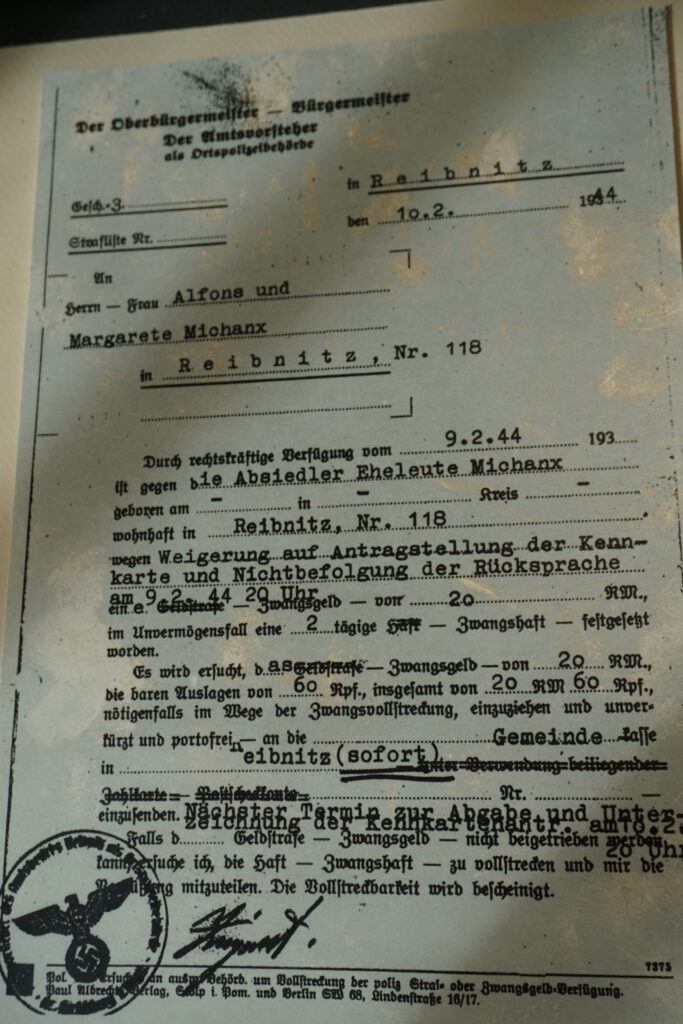

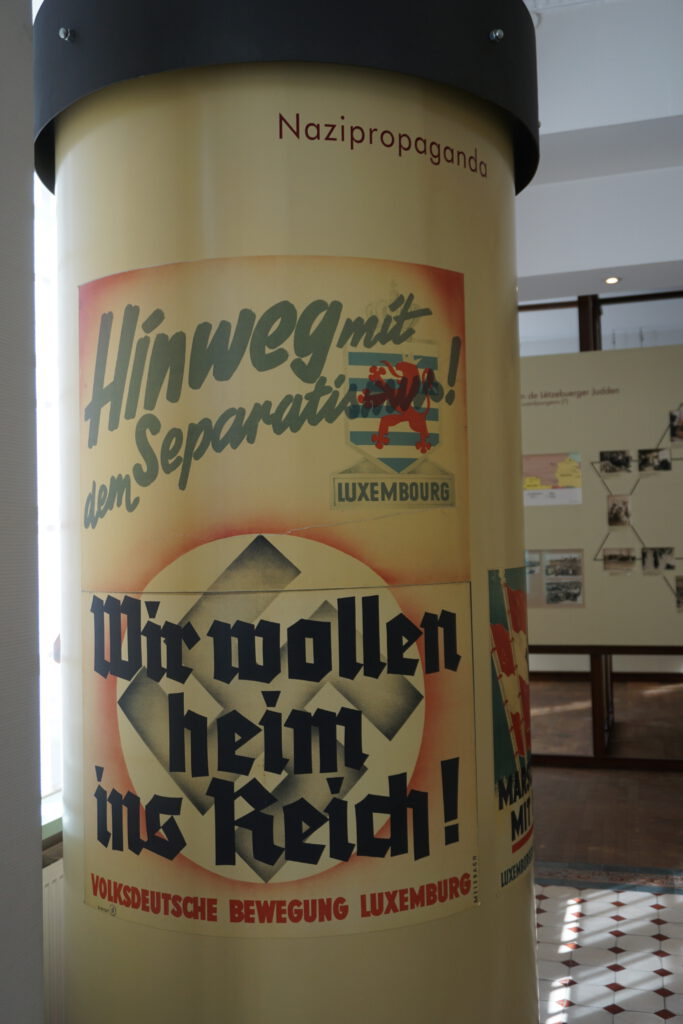

The families who had to leave their homes during the “Emmsiedlung” had very little time to gather a few belongings.

Their houses were taken by the Nazis and given to people working for them, or to families from other parts of the Reich who were regime-friendly … who, then,in turn had to flee after the liberation …

(picture of an official document, taken at the “Mémorial de la déportation” in Luxembourg-Hollerich )

In my studio, there are no shelves on the walls, only boxes of my stuff on the floor. Other people make a place their own as soon as they sign a lease, I, on the contrary, are ready to leave any time. Which isn´t a good feeling. And which often keeps me from making the work I want to make because of intense discomfort (the absence of functioning heating … e.g.) or because I am unable to spend long hours somewhere where I don´t feel “at home” … and so I run off again, to some other place that isn´t really mine …

I have lost a house to a divorce, already knowing while buying and restoring it, that the person I was doing it with was not someone any mentally sound person would stay with.

The fact that since last autumn I co-signed a lease on a garden allotment with a small garden hut on it, is a challenge, also because I am sharing this space and will have to make sure that this time I feel that it is mine as well and that I have the same rights and obligations then the others … As an artist with very small financial means, the tendency to feel inferior is, of course, ever present. Not having real money, not having a place that is mine, my subconscious probably means to protect me from the shock of loss of it all, but actually it prevents me from feeling secure and free.

Apartment in the Göhrenerstrasse in Berlin, I lived there from 2000 until 2008 when a water pipe in the apartment above ours burst and it took the firemen too long to find the main water valve in one of the cellars … we had to leave in a matter of minutes, getting our most important stuff out … and never returned … the place was inhabitable for months ….

The house. Bought and renovated in 2008. Left it to my former husband during divorce proceedings.

My paternal grandparents bought a house after the war and didn´t seem to be afraid of losing everything again … my parents had a house build in Gilsdorf, really big with a huge garden … it was a real home … my father sold it in 1994, three years after my mothers death. I never really said goodbye to the place, it was too hard to deal with all the conflicting emotions and the memories that clung to that place: a happy childhood, a garden I loved and spent a lot of time in, then, later, a place of conflict and illness , emptyness and sadness ….

I still haven´t figured out what makes a place a home. Maybe security and permance has less to do with it then I used to think. Since I manage to trust people I like to spend time in our apartment and to take care of our cats when we are away, I realize that it gives me a good feeling to have someone I can trust in our place and it makes me happy to know that someone else can make coffee and sit at our kitchen table and have a relaxing time there … Maybe sharing time and space with friends and family is a kind of home that I like … even though i am a very private person and need ( a lot of) time alone and a space that feels like mine alone …

My parents at their house in Gilsdorf. Where I grew up. My parents did a lot of work to design and build the garden on several levels themselves. I loved this garden. And only now do I appreciate how much work it must have been for them …

Having grown up with such a big garden means that I feel that outside living spaces are just as important as interior ones … I still have a tendency to feel locked in in houses with closed doors and windows and in appartments without much light …

Houses. Homes. Such an important and emotional and stress filled subject nowadays. Security seems to equal owning real estate. As if buildings make you immune to illness and death …

Still we all really need a place where we feel protected, safe, warm, dry … a home.

Soldinerstrasse. The only place I ever rented that was mine alone. 2009 – 2014. I used it as a studio mainly, but after the third rent increase I could not affort it anymore. I still miss that place.

That living space has become a commodity is nothing short of criminal.

When your home is causing you stress because you can hardly make ends meet and fear for your job constantly, then your home does not protect you anymore, on the contrary: it makes you sick. Greed, when it comes to housing, is so common that people just shrug their shoulders and pretend it is some kind of natural law that a few people are making insane, indecent amounts of money with a basic human need.

Smelling the flowers at my maternal grandparents house in Beggen. The garden they had was huge, and in my memory, I can always find my grandmother or in the kitchen or in the garden … She lived there until she died in 2001, nearly completely blind and deaf and with a body full of cancer, still she refused to leave that house until the end.

My grandmother from my fathers side spent her last years at a retirement home in Diekrich. She seemed very practical minded when it came to such things as what living arrangements were best for her … She was very social and being alone in a big house wasnot ideal for her.

Why have we accepted that people have to leave the cities they grew up in so that some guys who don’t even know how many buildings they possess can “invest” in some city … and “renovate” buildings in a way that they remain vacant afterwards because no one can pay the rent they are asking…? Or because they never meant to do anything but resell them anyway and don’t want to be bothered with tenants?

Our garden! It feels good to work on it, in it, to spend time there … and I am happy to share it with people I like.

… to be continued ….

picture taken in Hamm /Eifel long before my Dad was born (exact date unknown)

picture taken in Hamm /Eifel long before my Dad was born (exact date unknown) Meditating can provide an inner home (OMAC training weekend in Frankfurt a.M. 2012)

Meditating can provide an inner home (OMAC training weekend in Frankfurt a.M. 2012)